For adults with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)1

RETHINKING PBC MANAGEMENT

The fundamentals of PBC

PBC is a chronic, progressive autoimmune disease of the small bile ducts that is triggered by both genetic and environmental factors.2,3

Some of the most important prognostic markers of PBC include: ALP, GGT, bilirubin, ALT, AST, and fibrosis.4,5 Monitoring overall liver health—including, but not limited to, pathophysiology, disease progression, prognostic biomarkers, fibrosis, and treatment response—can help optimize patient outcomes in PBC.6

ALP alone is not sufficient as an indicator of disease progression4

A primary goal of PBC treatment is to prevent end-stage liver disease, liver transplant, or death. To achieve this goal, the focus should be4,7:

1.

Normalization, or near normalization, of key liver biomarkers6

2.

Prevention of fibrosis progression5

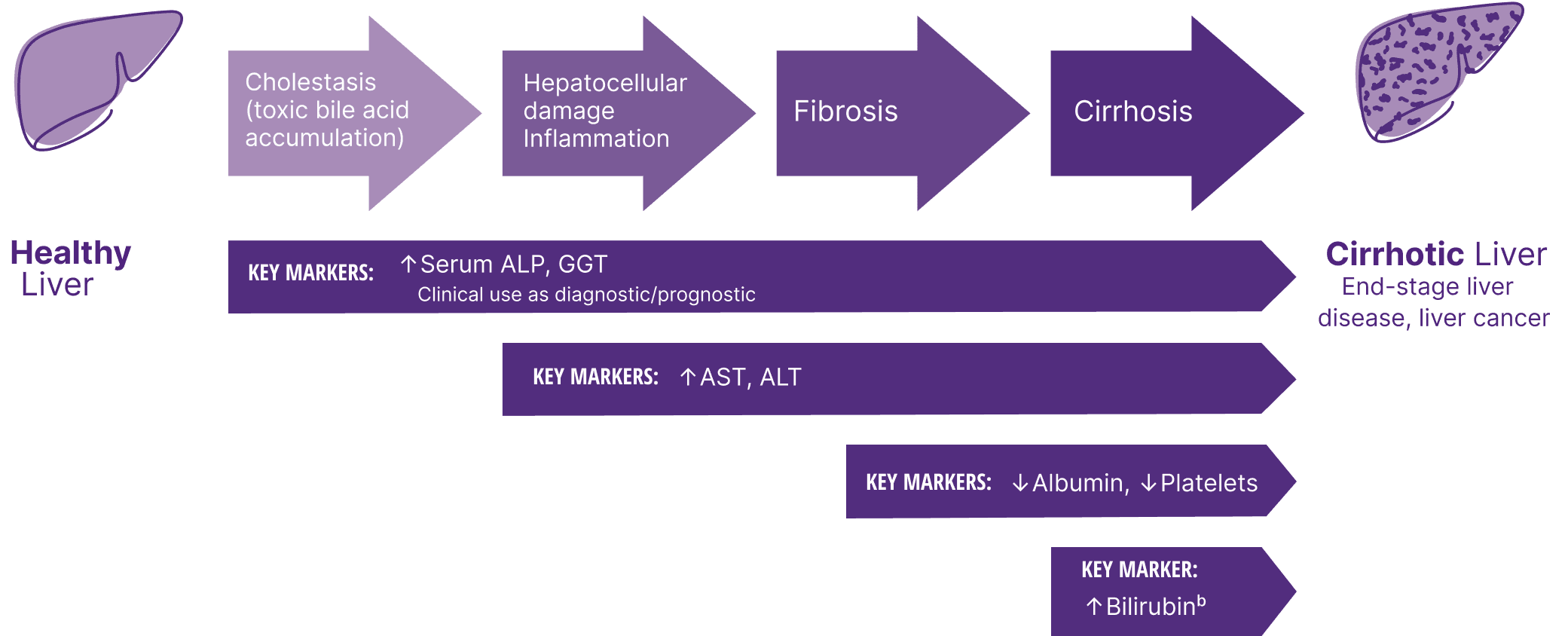

The path of PBC: Disease progression

With PBC, the focus should be on monitoring overall liver health6,8,a

aIn PBC, monitoring overall liver health includes, but is not limited to, pathophysiology, disease progression, prognostic biomarkers, fibrosis, and treatment response.6

bElevated bilirubin can also be a sign of severe cholestasis.4

Up to 30% of patients can have a severe, progressive form of PBC, resulting in early development of liver fibrosis and liver failure9

Some of the risk factors for disease progression include:

- Age at diagnosis (heightened risk for patients below 45 years of age)10

- Abnormal biomarker levels10

- Race (heightened risk for African American and Hispanic patients)11

- Advanced fibrosis5,10

Because experiences with PBC can vary from patient to patient, being aware of these specific risk factors can help you manage disease progression by determining an appropriate treatment plan for your patients.9,12-14

Consider a range of prognostic biomarkers13

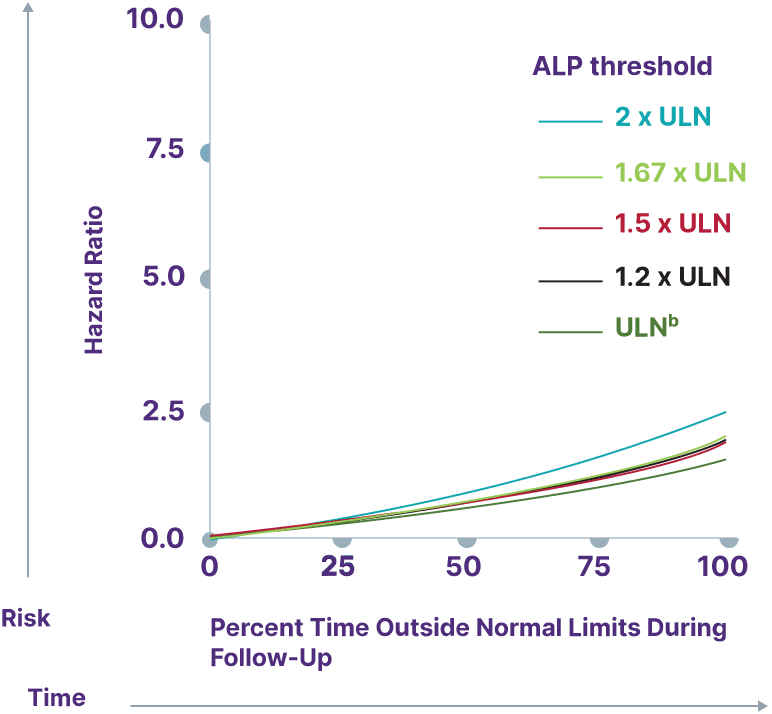

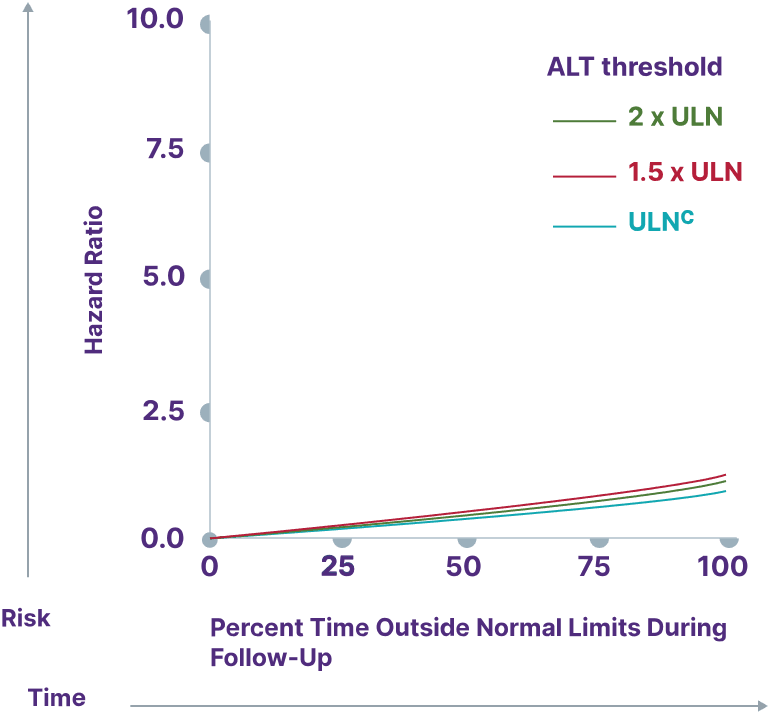

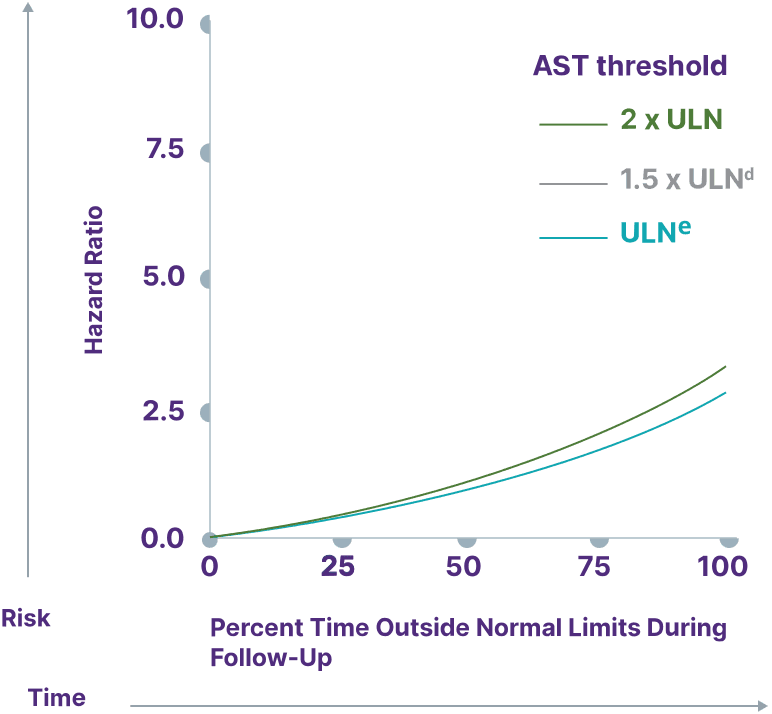

Increasing thresholds and time above ULN for ALP, ALT, and AST were associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes13,a

ALP

ALT

AST

Adapted from Kowdley K, et al. Poster presented at: EASL Congress; June 21-24, 2023; Vienna, Austria.

aData from a cohort of patients was created using the Komodo Health Map database with national laboratory data between January 1, 2014, and April 1, 2022. Patients were ≥18 years old with ≥1 inpatient PBC diagnosis claim or ≥2 outpatient PBC diagnosis claims separated by ≥30 days. Key exclusion criteria included history of hepatic decompensation, concomitant liver diseases (hepatitis C infection, hepatitis B infection, primary sclerosing cholangitis, alcoholic liver disease, Gilbert’s syndrome, hepatocellular carcinoma), liver transplant, comorbidities associated with abnormal biomarker levels, or use of obeticholic acid or fibrates (second-line therapies for PBC). Over the course of the study period, 77.7% of patients used UDCA. Adverse outcomes were defined as hospitalization for hepatic decompensation, transplant, or death.13

bALP ULN defined as 120 U/L.13

cALT ULN defined as 40 U/L.13

dULN and 1.5 x ULN have the same hazard ratio.

eAST ULN defined as 35 U/L for males and 30 U/L for females.13

A separate observational study demonstrated that GGT can also be used to increase the prognostic value of ALP measurement.15

THE IMPORTANCE OF BILIRUBIN

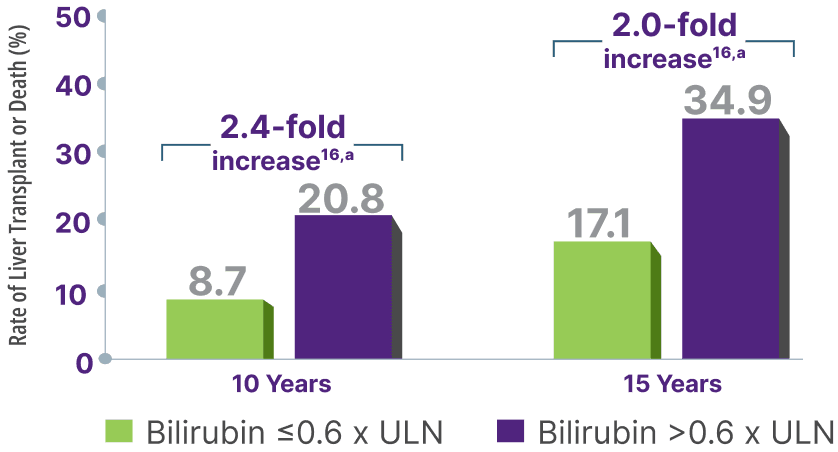

In 2 studies, bilirubin >0.6x ULN was associated with increased risk for adverse outcomes, including liver transplant or death.16,17

Surpassing the bilirubin 0.6 x ULN threshold significantly increased risk for liver transplant or death15,16,a

Adapted from Murillo Perez CF, et al. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2019.

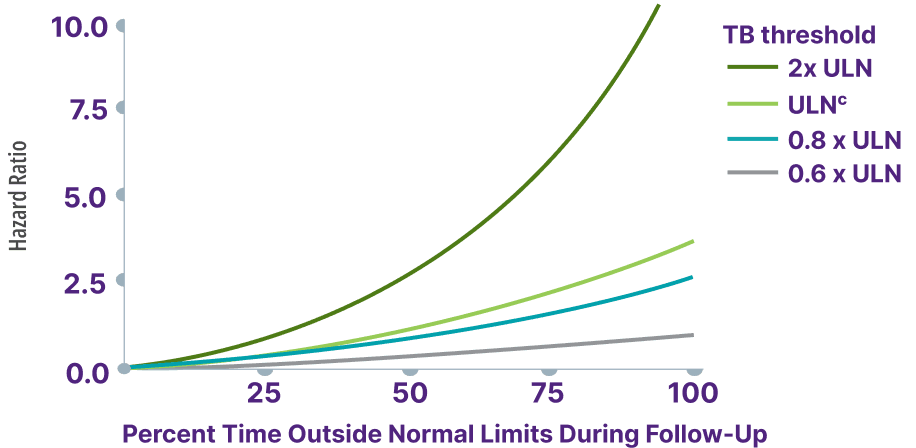

Total bilirubin >0.6 x ULN was associated with an increased risk for adverse outcomes13,b

Adapted from Kowdley K, et al. Poster presented at: EASL Congress; June 21-24, 2023; Vienna, Austria.

aCalculation based on percent rates of liver transplant or death extrapolated from survival estimate curve at 10 years.17

bData from a cohort of patients were created using the Komodo Health Map database with national laboratory data between January 1, 2014, and April 1, 2022. Patients were ≥18 years old with ≥1 inpatient PBC diagnosis claim or ≥2 outpatient PBC diagnosis claims separated by ≥30 days. Hazard ratio for risk of hospitalization for hepatic decompensation, transplant, or death.13

cTotal bilirubin ULN defined as 1 mg/dL.13

Fibrosis: Assessing the need for second-line therapy5

Advanced fibrosis (stages 3 and 4) was found to be an independent predictor of transplant-free survival in patients with PBC5,a

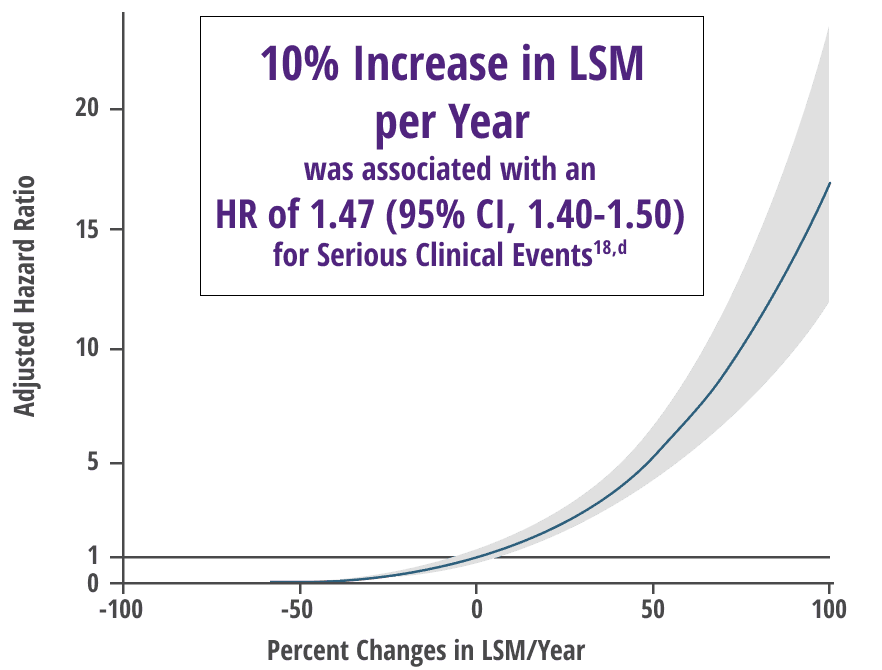

Any increase in LSM, as measured by TE, was associated with a significant increased risk of serious clinical events independent of prognostic biochemical markers18,b

Increase in LSM over time was correlated with inadequate response to UDCA (P=0.0017) in a subgroup analysis18

Adjusted relative risk of serious clinical event18,c

Adapted from Corpechot, et al. Oral communication presented at: EASL Congress; June 21-24, 2023; Vienna, Austria.

aAnalysis included 1828 patients with baseline liver biopsy that was performed from 1980 to 2014. Fibrosis was assessed histologically via liver biopsy and noninvasively via noninvasive markers of fibrosis.5

bFrom an international retrospective cohort study of 2244 patients with compensated PBC on UDCA therapy. Serious clinical event was defined as death, liver transplant, or liver complications.18

cHR (95% CI) according to annual relative change in LSM.

dFor the same age and gender.

In a separate study, FIB-4 >2.67 and APRI >0.5 were associated with increased risk for adverse outcomes13

Expert guidance on monitoring fibrosis

Per CLDF 2023 guidance, fibrosis staging using noninvasive tests (MRE or TE) is recommended soon after diagnosis. For patients with a more advanced fibrosis stage (VCTE or TE ≥10 kPa), compensated liver disease, and no signs of portal hypertension, the need for second-line treatment should be assessed at 6 months. Fibrosis surveillance is recommended at all stages of PBC.13

UDCA may not be enough for some patients8,19,20

AASLD expert guidance recommends monitoring patients every 3 to 6 months after initiating treatment with UDCA to determine whether they are achieving adequate lowering of ALP—and other key biomarkers of PBC.8

Up to 50% of patients may not achieve their treatment goals with UDCA alone.13

AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; APRI, AST to Platelet Ratio Index; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; CLDF, Chronic Liver Disease Foundation; FIB-4, Fibrosis-4; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; kPa, kilopascal; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; MRE, magnetic resonance elastography; TE, transient elastography; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; ULN, upper limit of normal; VCTE, vibration controlled transient elastography.

References

- OCALIVA full prescribing information. Morristown, NJ: Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2022.

- Poupon R. Primary biliary cirrhosis: a 2010 update. J Hepatol. 2010;52(5):745-758. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2009.11.027

- Cheung AC; Canadian PBC Society. Primary biliary cholangitis. National Organization for Rare Disorders. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/primary-biliary-cholangitis/3/. Updated 2020. Accessed March 17, 2023.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: the diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):145-172. doi:1016/j.jhep.2017.03.022

- Murillo Perez CF, Hirschfield GM, Corpechot C, et al. Fibrosis stage is an independent predictor of outcome in primary biliary cholangitis despite biochemical treatment response. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50(10):1127-1136. doi:10.1111/apt.15533

- Levy C, Manns M, Hirschfield G. New treatment paradigms in primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2023;21:2076-2087. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.02.005

- Ritter T, Hanson C, Fernandes C, et al. Duration and degree of alkaline phosphatase elevation is associated with significantly increased risk of death, liver transplant and hepatic compensation in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Poster presented at: Digestive Disease Week 2022; May 21-24, 2022; San Diego, CA.

- Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, Levy C, Mayo M. Primary biliary cholangitis: 2018 practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2019;69(1):394-419. doi:10.1002/hep.30145

- Younossi ZM, Bernstein D, Shiffman ML, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary biliary cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(1):48-63. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0390-3.

- Hirschfield GM, Chazouilleres O, Cortez-Pinto H, et al. A consensus integrated care pathway for patients with primary biliary cholangitis: a guideline-based approach to clinical care of patients. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15(8):929-939. doi:10.1080/17474124.2021.1945919

- Peters MG, Di Bisceglie AM, Kowdley KV, et al. Differences between Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic patients with primary biliary cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):769-775. doi:10.1002/hep.2175

- Onofrio FQ, Hirschfield GM, Gulamhusein AF. A practical review of primary biliary cholangitis for the gastroenterologist. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;15(3):145-154.

- Kowdley KV, Mayne T, Ness E, et al. Risk of death, liver transplant, or hepatic decompensation in primary biliary cholangitis increases with increased duration and degree beyond established clinical thresholds for hepatic biomarkers and fibrosis scores. Poster presented at: EASL Congress 2023; June 21-24, 2023; Vienna, Austria.

- Pate J, Gutierrez JA, Frenette CT, et al. Practical strategies for pruritus management in the obeticholic acid-treated patient with PBC: proceedings from the 2018 expert panel. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019;6(1):e000256. doi:10.1136/bmjgast-2018-000256

- Gerussi A, Bernasconi DP, O’Donnell SE. et al. Measurement of gamma glutamyl transferase to determine risk of liver transplantation or death in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2021;19:1688-1697. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.006

- Murillo Perez CF, Harms MH, Lindor KD, et al. Goals of treatment for improved survival in primary biliary cholangitis: treatment target should be bilirubin within the normal range and normalization of alkaline phosphatase. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;00:1-9. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000557

- Data on file: US-PB-MED-00492.

- Corpechot, et al. Oral communication presented at: EASL Congress; June 21-24, 2023; Vienna, Austria.

- Parés A, Caballería L, Rodés J. Excellent long-term survival in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):715 720. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.029

- Kuiper EMM, Hansen BE, de Vries RA, et al. Improved prognosis of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis that have a biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1281-1287. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.003